Meet Chip: Skin

The skin protects the body from dehydration and infection, and it helps regulate body temperature. The skin senses pain, pressure, hot and cold. When exposed to sunlight, the skin produces vitamin D, which is critical to good health.

Scientists are developing a tissue chip made of different types of skin cells that can mimic the skin’s responses to drugs to predict reactions of this sensitive organ. Having a laboratory-based system to test drugs for skin toxicity could lead to more accurate and quicker safety tests, enabling scientists to make new and safer drugs available to patients more quickly. Scientists also could use the chip technology to study skin disorders and find new treatments.

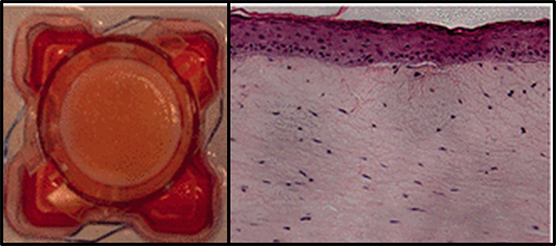

Skin on a Chip

NIH-supported scientists at Columbia University used a special technique to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Stem cells have the remarkable potential to develop into many different cell types. Stem cells are important during early life and for embryonic growth; in adults, stem cells function in tissue repair and maintenance. iPSCs can produce an unlimited supply of donor cells capable of forming skin and other types of tissues for the chip devices.

The scientists generated skin cells from iPSCs and demonstrated that the cells can be kept alive in a 3-D system. What’s more, the cells in the device transformed into different types of skin cells and organized themselves into layers that closely resembled actual human skin. The hope is to use this bioengineered system to learn more about how skin cells respond to various compounds so that researchers can better predict which ones might have toxic effects on the skin.

In addition, by using iPSCs from patients with skin diseases, researchers could use the resulting skin chips to learn more about the causes of the disorders and try different medicines as treatments.

Looking Ahead

NIH-supported researchers have shown that iPSC technology can be used to generate an organized system of skin cells on a tissue chip platform. Researchers could use the chip to test experimental drugs. In addition, the chip might enable researchers to gather the necessary data to accelerate the drug approval process and make new treatments available to patients faster.

Integrating the skin on a chip with chips based on other human organs may help scientists learn about potential drug side effects on skin and shed light on how drugs applied to the skin affect other organs of the body.